Aristotle’s originality with respect to Plato in conceiving that investigation of Nature which most closely corresponds to what we call ‘science’ is already evident in his earliest works, that is, in those written during the twenty years he spent at Plato’s school in the Academy (367–347 BCE). One of these is undoubtedly the Protrepticus, a work – now unfortunately lost – of exhortation to philosophy, which can be reconstructed at least in part from a similar Protrepticus composed by Iamblichus, a Neoplatonic philosopher active between the third and fourth centuries CE. Iamblichus’ work is a compilation made up of excerpts from Platonic dialogues, quoted almost verbatim, and exhortatory passages from lost works of Aristotle, which can legitimately be identified with the Protrepticus. It is assumed that these excerpts were reported faithfully and are therefore considered ‘fragments’ of that work. Chronologically, Aristotle’s Protrepticus is reliably dated to around 353 BCE, since the polemical tone of many of its arguments compared to those found in Isocrates’ speech Antidosis (On the Exchange of Goods), known to be from that year, suggests that Aristotle’s work was a reply to Isocrates – or vice versa.

From the Protrepticus it appears that Aristotle, like Plato, used the terms philosophía and epistḗmē almost interchangeably to refer to any form of knowledge, and attributed to the former the meaning of a way of life characterized by the pursuit of knowledge. In the Protrepticus, as in Plato, the term phrónēsis is also synonymous with philosophía and epistḗmē, although in Aristotle’s later works it would come to have the more specific meaning of practical wisdom (Ross 1955, fr. 4). Under the concept of philosophía or epistḗmē, Aristotle includes two types of ‘sciences’ (epistḗmai), namely those “concerning right and expedient things” and those “concerning Nature and the remaining truth” (perì phýseōs kaì tēs állēs alētheías).

Here we likely witness, for the first time, the distinction between theoretical and practical knowledge – a distinction that would become canonical in Aristotle’s mature works – and, above all, the emergence of the idea of a ‘science of Nature’, understood as an epistḗmē with an object defined as truth, i.e., regarded as true knowledge (ibid., fr. 5).

This clearly marks an original departure from Plato, for whom Nature – the realm of becoming – cannot be the object of true science due to its mutability, and is instead only suited to plausible discourse (eikós lógos, eikós mŷthos), i.e., discourse resembling science. True science, for Plato, is possible only with regard to the immutable intelligible world, of which the sensible world is a mere copy (Timaeus, 28a–29d). Breaking away from his teacher, Aristotle instead reconnects with the pre-Socratic tradition, which conceived philosophy primarily as the science of Nature, though broadly understood. Aristotle thus reasserts the possibility of a science of Nature after the crisis brought about by the Sophists, assigning it a narrower and more precise meaning than in the pre-Socratics.

In the Protrepticus, Aristotle conceives the science of Nature as knowledge of causes and of the principles or elements from which material bodies are derived or composed, explicitly naming them as fire, air, numbers, or “some other realities.” This is a clear reference to the pre-Socratic tradition, but does not exclude the position that held numbers as the principles of Nature – a view attributed both to the Pythagoreans and to Plato, who, as Aristotle reports, posited ideal numbers as principles of sensible realities (in which case the “other realities” might be the Ideas).

According to Iamblichus’ fragments – if reliable – Aristotle also reprises in the Protrepticus the doctrine found in Plato’s Laws, that all becoming things are produced either by Nature (phýsis), by art (téchnē), that is, human thought, or by chance (týchē). However, Aristotle modifies this view significantly: whereas Plato grants art – even if divine – primacy over Nature, since the sensible world is the work of a divine demiurge and thus Nature is the product of divine art, for Aristotle, Nature is not produced by any art, and human art is merely an imitation or completion of Nature (Ross 1955, fr. 11). This represents another element of the revalorization of Nature and a return to the pre-Socratic legacy, in opposition to the devaluation of Nature characteristic of Plato.

In the Protrepticus, Aristotle conceives Nature as characterized by a finalistic order, whereby everything within it exists for the sake of an end: eyelids, for example, exist to protect the eyes. The presence of an end is most evident in the products of art, but since art is an imitation of Nature, this makes the presence of an end in Nature even more plausible. Only realities produced by chance, according to Aristotle, lack an end. One can therefore distinguish realities according to Nature, which exist in view of an end, from realities contrary to Nature, which arise either by chance or from a perverse use of art (such as disease caused by a misuse of medicine, or destruction resulting from a corrupt application of the art of building).

Finalism is also admitted by Plato; however, for Plato it is the outcome of the conscious intent of a demiurge who orders all things toward their ends. By contrast, for Aristotle it is an order immanent in Nature itself, whereby every natural being tends toward its own end, which is its good – that is, its perfection. This principle applies to all living beings – plants and animals – and most notably to man, the most perfect being, whose end, according to Aristotle, is knowledge. To support this view, Aristotle cites Pythagoras and Anaxagoras, once again indicating his deliberate engagement with the pre-Socratic tradition.

Moreover, in the Protrepticus, Aristotle uses – perhaps for the first time – the phrase “Nature and god have begotten us for this purpose,” which might suggest continued dependence on the Platonic view that man and Nature are products of a divine creator. This expression, however, is best understood as metaphorical rather than literal. This is evident from another lost work by Aristotle, the dialogue On Philosophy, also likely written during his years at the Academy, in which he takes a firm stance in favor of the eternity of the world, opposing Plato’s doctrine in the Timaeus. Our knowledge here relies on Philo of Alexandria (1st century BCE – 1st century CE), who in his On the Eternity of the World quotes fragments from Aristotle’s writings that can reasonably be identified with this dialogue; his testimony is also corroborated by Cicero, who certainly knew the work in question.

From the fragments of On Philosophy, we learn that Aristotle conceived the world as a whole – the heavens, stars, and Earth – as ungenerated and indestructible, that is, eternal and therefore also divine (Ross 1955, frr. 18–20), though subordinate to a supreme transcendent god. He distinguished, however, between the eternity of celestial bodies – which appear incorruptible and are eternally moved in circular motion – and that of terrestrial bodies, which are individually perishable and mutable, and therefore eternal only in terms of their species. To explain this distinction, it seems that already in this dialogue, as later in his mature works, Aristotle maintained that terrestrial bodies are composed of the four elements of the pre-Socratic tradition – earth, water, air, and fire – which can mix and transform into one another, while celestial bodies, i.e., the stars and the heavens, are composed of a fifth element, aithḗr, which is immutable and incorruptible (ibid., frr. 19–21).

Since Philo’s fragments also refer to a god as the creator of the world, this should either be understood metaphorically or attributed to another speaker in the dialogue – possibly Plato himself. It is certain that Aristotle interpreted the demiurge in the Timaeus as a craftsman responsible for a temporal origin of the world, which contradicts the eternity he ascribes to the world.

In On Philosophy, as reported in a famous passage by Cicero, Aristotle also conceived of the sky and its stars as revolving around the Earth, attributing this circular motion to the influence of a supreme god understood as noûs – pure intellect, non-material, and thus transcendent with respect to the world (ibid., fr. 26). Since the movement of the heavens and stars governs all changes on Earth, especially the cycle of the seasons and the processes of generation and corruption among living beings, this supreme god could be said to be the cause of the world’s order – that is, the cause of its finalism. However, this does not mean that the supreme god is the end of all that happens in the cosmos, since – as seen already in the Protrepticus – each being has as its end the perfection of its own nature.

It appears that in On Philosophy (fr. 28), Aristotle also reflected on this idea of finalism, as he himself refers in Physics (194a 27–36) to this dialogue as the place where he first distinguished two meanings of the term ‘end,’ a distinction that would recur throughout his works. According to this distinction, the end is, in the first sense, that for the sake of which a change occurs – the ultimate goal toward which the change is directed, that is, the good or perfection of the changing entity. In the second sense, the end is that which benefits from the change – the subject that uses other things for its own purposes (e.g., man, who uses natural entities such as elements, plants, and animals as though they existed for him, although their primary end, in the first sense, is their own perfection).

Thus, while it is legitimate to speak of a return to pre-Socratic naturalism in Aristotle’s lost works, his conception of Nature, though reminiscent in some respects of Anaxagoras – especially in its acknowledgment of a transcendent Intellect as the principle of cosmic order – differs substantially in its pronounced finalism, which appears to respond directly to Plato’s criticism of Anaxagoras in the Phaedo (97c–98b). Aristotle’s finalism, however, diverges from Plato’s in that it does not rely on a demiurgic act of shaping, but on the combined action of multiple principles: the prime mover and the intrinsic tendency of natural beings to actualize their own good.

The logical works, traditionally grouped under the title Organon (meaning ‘instrument’), reflect the idea that logic serves an instrumental function for the sciences proper. These include six works: Categories, On Interpretation, Prior Analytics, Posterior Analytics, Topics, and Sophistical Refutations. Of these, only the final part of On Interpretation and the Prior Analytics contain what we now consider formal logic – a theory of valid inference in the sense of predicate logic – and this branch of logic is not merely an instrument but a science in its own right. Nevertheless, semantics (Categories), philosophy of language (On Interpretation), the theory of scientific method (Posterior Analytics), and dialectical argumentation (Topics and Sophistical Refutations) are all encompassed within Aristotle’s broader concept of logic. Although all these works are relevant to the history of science, this discussion will, for brevity, set aside Categories, On Interpretation and Prior Analytics, which concern specific scientific domains, and focus instead on the Posterior Analytics and Topics, where Aristotle formulates methodological principles pertinent to natural investigation.

In the Posterior Analytics, Aristotle presents his general concept of science (epistḗmē), which applies both to what we call the natural sciences – such as physics, chemistry, and biology – and to the so-called exact sciences, i.e., the mathematical sciences, as well as to what he considers first philosophy. The defining characteristic of science, according to Aristotle, is that it is not merely knowledge of facts or states of affairs, but knowledge of causes – that is, explanations of facts. In some cases, the cause in question is fully sufficient to explain the fact, which, in light of that cause, is revealed to occur necessarily, such that things “cannot be otherwise.” This is the case for the mathematical sciences, which, more than any other, seem in the Posterior Analytics to represent the model of science for Aristotle. This level of necessity may not be attainable in other sciences, where the connection between a fact and its cause is not equally necessary.

What guarantees the connection between cause and effect, as well as its necessity, is what Aristotle calls “syllogism” – though it is perhaps more accurate to describe it generally as deduction, that is, valid inference or argumentation from more general premises to less general conclusions. Syllogism is a specific type of valid inference, and Aristotle develops a detailed theory of it in the Prior Analytics. When the inference proceeds from true premises that are better known than the conclusion, logically prior to it, and actually cause it, the inference is called a “demonstration,” and the premises are termed “principles” (Analytica posteriora, I, 2). Science, then, is for Aristotle essentially a “demonstrative disposition”: the possession of a system of interconnected notions grounded in actual demonstrations. The model for this conception of science was undoubtedly geometry, in the form that would later be codified by Euclid (already active in Aristotle’s time), with its premises (definitions, axioms, postulates), its demonstrations, and its conclusions (theorems).

Demonstrations – that is, scientific deductions – must always proceed within a single genus of objects: numbers in the case of arithmetic, or magnitudes in the case of geometry. In other words, they must derive from premises that are proper to that genus – the so-called “proper principles.” For Aristotle, these include the assumption of the object’s existence (i.e., the affirmative answer to the question “whether it is”) and the definition of its essence (the characterizing answer to the question “what it is”). For instance, the proper principles of arithmetic involve the existence and definitions of numbers, and those of geometry involve the existence and definitions of magnitudes. Based on these principles, one can demonstrate that certain necessary properties belong to the object (Analytica posteriora, I, 7) – for example, that every triangle has internal angles summing to two right angles.

In addition to their own principles, scientific demonstrations also rely on so-called “common principles,” or axioms – premises shared by several sciences. These include, for example, the principle that subtracting equal quantities from equal quantities yields equal quantities (common to all sciences dealing with quantities, such as mathematics and physics), or principles common to all sciences, such as the “principle of non-contradiction” (two contradictory propositions – i.e., the affirmation and denial of the same predicate of the same subject – cannot both be true at the same time and in the same respect) and the “principle of the excluded middle” (between two contradictory propositions, one must be true and the other false; there is no third possibility) (ibid., I, 11).

It is clear that mathematics – encompassing arithmetic and geometry – serves as the model for this conception of science. Yet, according to Aristotle, demonstrations are also possible in other sciences, including the so-called applied mathematics (e.g., harmonics, optics, mechanics, and astronomy), and even in physics, both terrestrial and celestial. This is evidenced by a well-known distinction introduced in the Posterior Analytics between the demonstration of the “why” and the demonstration of the “that.” The former is the exemplary kind, deducing an effect from its cause (e.g., theorems about triangles from the definition of triangle). But this is not always possible, as the effect is sometimes better known than its cause. In such cases, one must proceed in the reverse direction: the result is a demonstration of the “that,” which proves that a certain fact holds necessarily, though not by deducing it from its cause. Aristotle’s example is the proximity of the planets to the Earth inferred from the fact that they do not twinkle. The latter is actually an effect of their proximity, not its cause, but since it is better known, it can serve as a basis for a “that” demonstration (ibid., I, 13).

Aristotle observes that sometimes the same proposition can be the subject of both types of demonstration. For instance, propositions addressed by applied mathematics are demonstrated in that field via “that” demonstrations, whereas pure mathematics (arithmetic and geometry) can demonstrate them via “why” demonstrations. This implies that applied mathematics is logically subordinate to pure mathematics, as it deals with phenomena whose causes lie in the latter.

The demonstration of the “that” resembles a type of deduction practiced by contemporary mathematicians, known as “analysis,” which involves solving a problem by assuming, hypothetically, a yet-unknown solution and deducing from it the consequences, until one arrives at a proposition already known to be true. Aristotle notes that this method works well in mathematics, where propositions are convertible, but it is less reliable in fields where such convertibility does not hold (ibid., I, 12). A special case of analysis, typical of the physical sciences, is demonstration based on “hypothetical necessity” – that is, assuming the existence of a given effect and deducing the necessary conditions for its realization (Physica, II, 9; De partibus animalium, I, 1, 639b 30–640a 8). A similar method is employed in the process of deliberation (Ethica Nicomachea, III, 3), which identifies the means required to achieve a given practical end.

Aristotle also theorizes another form of demonstration: reductio ad absurdum, or demonstration “by impossibility,” which proves a thesis by assuming the contrary and showing that this leads to impossible or contradictory consequences. The contradiction reveals the falsity of the assumption, and thus, by the principle of the excluded middle, the truth of its negation (Analytica posteriora, I, 26).

It is also worth noting that in the Prior Analytics – the treatise focused on the specific type of deduction known as syllogism – Aristotle addresses other forms of inference or argumentation that, while not demonstrative, may still be employed in the sciences. Particularly important is induction (epagōgḗ), the inference of a universal conclusion from multiple particular cases. For example, from the fact that men, horses, and mules – animals without bile – are long-lived, one may infer that all animals without bile are long-lived (Analytica priora, II, 23). While these premises are not sufficient to prove the conclusion, their relative familiarity makes the conclusion at least plausible.

Both deduction and induction have weaker variants: the enthymeme and the example, respectively. The enthymeme is an inference based on probable premises (eikóta) – statements valid in most cases – or on “signs.” These signs may be necessary (i.e., necessarily connected to what they signify), thus serving as genuine evidence, or unnecessary, thus functioning merely as suggestive clues. For instance, a woman having milk is a necessary sign of childbirth and provides valid evidence, whereas being pale is not, making the inference merely circumstantial (ibid., II, 27; Rhetorica, I, 2). The example is a form of induction from a single case – for example, arguing that making war on one’s neighbors is harmful because it was harmful for the Thebans to do so against the Phocians, who were their neighbors (Analytica priora, II, 24).

Moreover, deduction can serve not only to establish a thesis but also to refute it. This is the case with refutation (élenchos), defined as “the deduction of a contradiction,” that is, a conclusion that contradicts another premise accepted as true. By the principle of non-contradiction, such a deduction invalidates the thesis from which the contradiction was derived (Analytica priora, II, 20). Another way to disprove a thesis is through objection (énstasis), or counterexample – that is, the citation of a particular case acknowledged as true, which contradicts a given general thesis. While a single example cannot prove a general proposition, it is sufficient to disprove a universal claim that it opposes (ibid., II, 26).

In the Posterior Analytics, alongside the theory of demonstration, Aristotle also elaborates a second fundamental logical operation: definition. Definitions serve as the starting points for demonstrations and are thus indispensable to scientific inquiry. A definition is the discourse that expresses the “essence” of an object – that is, the answer to the question ‘what is it?’ It identifies both the genus to which the object belongs (e.g., in the case of man, the genus “animal”) and its specific difference, i.e., the property that is common to all members of that species and distinguishes them from those of other species (e.g., in the case of man, “bipedal,” or more precisely “rational bipedal animal”).

Since, for Aristotle, the essence is the “formal cause” of an entity – what makes it be what it is – the best kind of definition is the one that points to this cause. One example he offers is drawn from physics: thunder is defined as “the noise caused by the extinction of fire in the clouds” – a definition that explicitly identifies its cause (Analytica posteriora, II, 10). Another example is that of an eclipse, defined as the absence of light on the Moon due to the interposition of the Earth (ibid., I, 31). Given that Aristotle distinguishes four types of causes – formal, material, efficient, and final – the definition underpinning a scientific demonstration may refer to any of these. Thus, demonstrations can be based on the formal or final cause (which Aristotle treats as equivalent in some contexts), but also on the efficient or material cause (ibid., II, 11).

Definitions cannot be derived through demonstration, as they serve as its starting points. However, they can be arrived at through alternative methods, such as dividing a genus into species and identifying the specific differences among them (ibid., II, 13), or through induction, by observing a distinguishing feature common to all members of a species in particular cases (ibid., II, 19). In the Topics, Aristotle further suggests that the principles of individual sciences – including definitions – can be discovered dialectically. In other writings, he frequently emphasizes the role of dialectic in identifying foundational principles.

Dialectic, for Aristotle, is the art of arguing correctly, either by attacking an opponent’s thesis or defending one’s own from attack. Refutation proceeds by attempting to deduce a contradiction from the opponent’s thesis, while defense involves avoiding such a refutation. Dialectical refutation employs “dialectical syllogisms” – deductions that, unlike scientific demonstrations, proceed from éndoxa, i.e., premises accepted by all, or by most people, or by recognized experts in a given field (Topica, I, 1). While éndoxa are not sufficient for scientific demonstration, they suffice for constructing arguments effective in public debate, because they are shared by the interlocutor and the audience, who act as judges. When applied within a scientific community, éndoxa function similarly to what we now call “paradigms” – scientific worldviews characteristic of a specific era. As a result, the refutation of a thesis, even when based on éndoxa, is often equivalent to a demonstration of its contrary (Ethica Eudemia, I, 3, 1215a 5–7). Likewise, the defense of a thesis – achieved by answering all objections and showing its coherence with most éndoxa, or at least with the most authoritative ones – is considered by Aristotle as equivalent to a sufficient demonstration (Ethica Nicomachea, VII, 1, 1145b 1–7). Hence, dialectic is useful not only for prevailing in public discussions but also for the practice of the sciences, as it enables one to distinguish truth from falsehood and, crucially, to establish the principles of the sciences – principles that cannot themselves be demonstrated (Topica, I, 2). On rare occasions, Aristotle even refers to “demonstration by refutation,” for instance in defending the principle of non-contradiction by refuting its denial, thereby appearing to equate dialectical procedures with scientific demonstration (Metaphysica, IV, 4).

The search for the principles of the individual sciences – that is, definitions – generally begins with what Aristotle calls the phainómena, literally “the things that appear.” These can be of two kinds. First, they may be phenomena that appear to the senses – facts observed through sensible perception – which are the basis of empirical experience. For example, the motions of the planets are the phenomena from which astronomy proceeds (Analytica priora, I, 30; Analytica posteriora, I, 13). Second, they may be things that appear to be true to some people – that is, the opinions or beliefs of individuals or groups. For instance, what people think about certain vices or virtues constitutes the phenomena from which ethics begins (Ethica Nicomachea, VII, 1). In the case of the first type, the aim is to investigate their causes; in the case of the second, it is to assess whether the beliefs are true or false. In both instances, inquiry proceeds by formulating problems – that is, positing opposing answers – and then deducing their consequences to see which are compatible or incompatible with either empirical observations or widely accepted éndoxa.

Aristotle employed a wide range of observations, some direct and accurate – such as those concerning the mole’s visual system or the configuration of animal dentition – and others indirect and inaccurate, reported by others. For instance, he uncritically repeats claims that testaceans are eyeless, that women have fewer teeth than men, and that certain insects arise spontaneously from earth. He often compiled as much information as possible without always subjecting it to rigorous scrutiny – partly because verification was not always feasible. His sources included empirical data, previous literature, the reports of experts (e.g., fishermen, hunters, travelers), and, at times, mere hearsay. He appears to have conducted dissections himself, at least on certain animals such as fish and birds, and made repeated, systematic observations of chick embryo development, reportedly identifying the early formation of the heart. It is also plausible that he engaged in simple experiments; for example, to illustrate why ships float more easily on the sea than on rivers, he cites the buoyancy of eggs placed in saltwater – demonstrating the effect of salinity.

A much-debated issue among modern scholars concerns whether Aristotle, in his scientific treatises, consistently follows the methodological guidelines laid out in the Posterior Analytics. Specifically, does he perform actual demonstrations as defined therein? Some interpreters have argued that the methods employed in the scientific treatises diverge entirely from the demonstrative structure theorized in the Analytics, and have therefore interpreted the latter as a theoretical account of science already established and organized into an axiomatic-deductive system, perhaps intended for pedagogical purposes. More recent scholarship, however, has emphasized that Aristotle articulates a plurality of methods in the Analytics, and that in his scientific treatises he alternates between them – sometimes pursuing definitions, sometimes constructing actual demonstrations, and sometimes engaging in observational or dialectical procedures (Lloyd 1996).

Moreover, Aristotle himself frequently distinguishes between varying degrees of demonstrative rigor (akríbeia): (1) absolute rigor, characteristic of the mathematical sciences, which proceed from premises that are universally and necessarily true (Metaphysica, II, 3); (2) a more flexible rigor (malakóteron), proper to the natural and practical sciences, which deal with what is true “for the most part” (ibid., VI, 1); and (3) the rhetorical level of reasoning, which relies on examples or testimony (Ethica Nicomachea, I, 3). Thus, rather than positing a rigid dichotomy between the logical works and the scientific treatises, it is more accurate to say that the treatises apply, case by case, one or another of the multiple methodological strategies theorized by Aristotle in the logical corpus and in other methodological passages dispersed throughout his works.

The works on physics included in the Corpus Aristotelicum comprise those that follow the logical treatises and precede the Metaphysics – so named by later editors precisely because they were placed “after” the works on physics. Excluding the apocryphal texts, these include: Physica, De caelo, De generatione et corruptione and Meteorologica, which address, respectively, Nature in general, celestial phenomena, terrestrial phenomena, and atmospheric phenomena; De anima and the Parva naturalia, which concern the soul – understood broadly as the principle of life – and its functions; Historia animalium, De partibus animalium, De motu animalium, De incessu animalium and De generatione animalium, which focus on animals; and a group of minor works of uncertain authenticity, also dealing with natural issues, such as De coloribus, De audibilibus, Physiognomica, De plantis, Mirabilium auscultationes, Mechanica, Problemata, De lineis insecabilibus, De ventorum situ et nominibus.

As these titles suggest, by “physics” Aristotle meant the study of all of Nature – both inanimate and living – including human beings. This investigation encompassed, in broad terms, everything that in modern science falls under not only physics proper but also astronomy, geology, chemistry, biology, and psychology. Crucially, this study is no longer, as in Plato, merely a matter of plausible discourse; for Aristotle, it is a true science – epistḗmē – that is, knowledge of causes. Though its methods are less rigorous than those of mathematics, it is nonetheless a science distinct from “first philosophy,” later called metaphysics, which deals with being as such and with the primary causes of things, including immaterial and unmoving causes. Since the pre-Socratics lacked a clear conception of metaphysics in this sense, Aristotle’s approach marks a decisive turning point – it is no exaggeration to say, as has often been claimed, that with Aristotle, physics as a science was born.

At this point, it is useful to recall Aristotle’s famous classification of the sciences. Sciences (epistḗmai) – or “philosophies” (philosophíai), terms which he uses interchangeably – are divided into three categories: (1) theoretical, aimed at knowledge (theoría); (2) practical, aimed at action (prâxis); and (3) poietic, aimed at production (poíēsis). The theoretical sciences are further subdivided into: (a) first philosophy, which studies being as being – that is, the totality of reality – and its primary causes, including immaterial ones; (b) physics, or “second philosophy,” which investigates Nature, i.e., sensible and changeable entities; and (c) mathematics, which studies the quantitative aspects of physical reality – numbers and magnitudes – which, once separated by abstraction, can be treated as immobile and thus with greater rigor than in physics (Metaphysica, VI, 1). This hierarchy reflects the dignity of the objects studied, whereas the actual sequence of learning and research – also reflected in the ordering of Aristotle’s works – begins with physics and ends with first philosophy.

Aristotle further clarifies the difference between physics and mathematics through a famous example: consider a nose with an upward curvature that makes it “snub” or “camused.” The notion of camused pertains to physics because it cannot be separated from the material substrate – the nose. By contrast, the notion of curved is mathematical, as geometry can study curvature independently of the matter in which it inheres. Some sciences, such as optics, harmonics, mechanics, and astronomy, occupy an intermediate position between physics and mathematics: they deal with quantitative aspects of physical bodies – such as the Earth’s spherical shape – but without detaching entirely from their material substrate (Physica, II, 2).

Nature (phýsis), for Aristotle, is the totality of “natural” entities – those that contain within themselves the principle of motion and rest (Physica, II, 1). This definition identifies natural beings as entities capable of movement and change by their own inherent power, unlike artificial products, which are made by humans and thus lack this internal principle. Natural entities include bodies composed of the four elements (earth, water, air, fire), as well as plants and animals. A general property of Nature, therefore, is motion (kínēsis), or more broadly, change (metabolḗ) – a change intrinsic to the entity, arising not from external causes but from its own nature. To analyze change, Aristotle identifies its indispensable elements: the “substrate” (hypokeímenon), or matter (hýlē), which is what undergoes change; the “form” (eîdos or morphḗ), which is the actuality acquired at the end of change; and “privation” (stérēsis), the absence of that form, i.e., the initial condition of the substrate prior to transformation (Physica, II, 1).

Physics must investigate the causes of natural entities, which fall into four types: (1) material cause – the matter composing a thing, coinciding with the substrate of change; (2) formal cause – the structure or arrangement of a thing, akin to a “formula” in modern chemistry; (3) efficient (or moving) cause – the source of change, the agent that initiates transformation; (4) final cause – the end or purpose toward which the change is directed, which often coincides with the form (Physica, II, 3). These are not four distinct things but four explanatory dimensions of reality. Aristotle insists that physics must investigate all four, though he considers the formal and final causes the most important. The final cause, in particular, is the natural terminus of change – such as the “natural places” of inert bodies, or, in the case of living beings, the attainment of maturity, generally expressed in reproductive capacity.

Closely related to final causality are Aristotle’s concepts of chance (autómaton) and fortune (týchē). Chance is the deviation of a process from its natural end, due to the intervention of an accidental factor – something concomitant but not essential to one of its causes. Fortune is the same phenomenon within the domain of human action (Physica, II, 4–6). Also connected is the idea of hypothetical necessity – the necessity of antecedent conditions in light of their effect, which is also their natural end. For instance, nutrition, climate, and medication are necessary for health; fertilization, gestation, and development are necessary for reproduction (Physica, II, 9).

Particularly notable is Aristotle’s general definition of motion (understood as any kind of change): “the actuality of what is in potentiality, insofar as it is in potentiality” (Physica, III, 1). Potentiality (dýnamis) is the real and determinate possibility of acquiring a form not yet possessed. Motion is thus the actualization (enérgeia) of this capacity – it is the process by which potential becomes actual. Only what is in potential can undergo change, and everything that changes contains potentiality. However, it is not any aspect of the changing thing that is actualized in motion, but precisely the aspect in which it was potential. For Aristotle, then, motion is not a state – as rest is, and as uniform rectilinear motion would later become in modern mechanics – but a transition from one state to another.

In the Physics, which is devoted to the study of Nature and thus of change in general, Aristotle explores the characteristics and conditions of change. The first such characteristic is infinity (ápeiron). Unlike the Pre-Socratics – Anaximander or possibly the Pythagoreans – Aristotle does not consider the infinite to be an actual body or substance, nor, as Plato did, a principle of reality in act (like the “indefinite dyad”). Rather, for Aristotle, the infinite is a process – a reality always in potentiality. To clarify his meaning, it is helpful to render ápeiron and its opposite not as “infinite” and “finite,” but as “unfinished” and “complete.” The infinite is what is never complete – such as the process of division to which a magnitude (e.g., a line) is susceptible, which is infinitely divisible, or the process of addition that generates the series of numbers, which is infinitely augmentable (Physica, III, 4–8).

Aristotle therefore does not deny, as is often claimed, the existence of the infinite or the usefulness of this concept. What he does deny is that the universe is infinite or that infinity is one of the fundamental principles from which all things derive. Instead, he admits the infinite character of certain operations – such as division and addition – and, to some extent, of certain realities, such as motion and time, which, as we shall see, he regards as eternal, that is, without beginning or end. When Aristotle states that the universe cannot be infinite, it is because he conceives of it as a sensible quantity, and no matter how vast a quantity may be, it must always remain finite.

Closely connected to his conception of the infinite is Aristotle’s theory of place (tópos). Unlike Plato, Aristotle does not analyze space as such, since he does not admit the existence of infinite space. Instead, he focuses on place – that is, the portion of space contained within a boundary – and defines it as “the inner boundary of the containing body” (Physica, IV, 4). The totality of space is delimited by the universe itself, whose outermost boundary is conceived by Aristotle as the “first heaven,” an extreme sphere encompassing all other things. Beyond this, there is neither place nor space; hence, the universe is not “in” a place. The significance of this doctrine lies in its relational conception of space: space is not an absolute reality, as it would be in Newtonian physics, but is always defined in relation to bodies.

From this notion derives Aristotle’s famous doctrine of natural places, according to which bodies composed of water and earth naturally move downward, while those made of air and fire naturally rise. “Downward” is defined as toward the center of the universe – coinciding with the center of the Earth, which, for Aristotle as for nearly all ancient cosmologists except the Pythagoreans, lies at the center of the cosmos. “Upward” is toward the region nearest the outermost sphere – the heavens (Physica, IV, 1). To account for this tendency, Aristotle attributes the property of heaviness to earth and water, and lightness to air and fire.

This conception of place also grounds Aristotle’s doctrine of the impossibility of a vacuum – not the impossibility of creating a vacuum artificially within a vessel, but rather the absence of vacuum in nature. For Aristotle, the universe is filled with matter, distributed among various elements, and the motion of bodies within it does not require the existence of a void, contrary to the views of Democritus. Rather, motion occurs as it does when solid bodies move through liquids (Physica, IV, 7). One argument Aristotle offers against the existence of vacuum is that bodies not continuously acted upon by a mover eventually come to rest – demonstrating the existence of a medium, such as air, within which they move and which resists their motion. Were they moving through a vacuum, he contends, they would never stop (Physica, IV, 8).

This observation reveals that Aristotle’s universe is always that of the senses, and his mechanics are, in some respects, more consistent with our perceptual experience than modern physics. While Aristotle rejects the idea of motion in a vacuum as completely unreal, he nonetheless anticipates the principle of inertia in recognizing that, if no resistance existed, bodies in motion would never come to rest. Similarly, his claim that the speed of falling bodies is proportional to their weight – which was famously refuted by Galileo in the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems – reflects the world of experience, where no vacuum exists. Aristotle himself writes, “If a vacuum were admitted, all bodies would move with the same velocity” (Physica, IV, 8, 216a 11–21) – once again hinting at an intuition resembling the principle of inertia. But, he immediately adds, “this is impossible.”

Aristotle’s lack of a principle of inertia made it difficult for him to explain the motion of projectiles – a problem that would later be addressed by the theory of impetus, first proposed by the late antique commentator John Philoponus (d. c. 576), and later developed by the medieval physicist John Buridan (14th century). According to Aristotle, a projectile continues to move after being released from its mover because it is pushed along by the surrounding air, which is itself moved by the initial mover and in turn propels the object toward its natural place with a speed greater than its own. This account shows that for Aristotle, motion can only be caused by direct contact between mover and moved; as such, he is unable to explain motion at a distance.

Another important concept related to motion, analyzed by Aristotle in the Physics, is that of time. On this topic, he develops Plato’s earlier analysis – which identified time with the movement of the heavens – by clarifying that while time is indeed linked to change (since change cannot be perceived without it), it does not coincide with it, because different movements can occur simultaneously. Time is an aspect of motion: specifically, it is “the number of motion in respect of before and after” – that is, its measure in terms of succession (Physica, IV, 11). As such, the concept of time, like that of place, is relational: time is, on one hand, relative to movement, which it measures, and, on the other, relative to the soul – that is, to the perceiving subject – without which there would be no measurement (Physica, IV, 14).

Criticisms that accuse Aristotle of conceptualizing time as spatialized are thus misplaced. It is true that Aristotle uses the geometric notion of a point to elucidate the concept of the “instant” or “now” (nŷn), which serves as the boundary between past and future and allows the perception of succession – even though the instant itself does not belong to time and is not time (Physica, IV, 12). Nevertheless, Aristotle clearly distinguishes time from space by affirming the irreversibility of time. He even characterizes it in quasi-existential terms, asserting that time “wears everything away” – that is, it ages all things – and, in a sense, sets them outside of itself; time, he says, is “ecstatic” (Physica, IV, 13).

Also of particular importance is Aristotle’s classification of different kinds of change (metabolḗ), which demonstrates the concept’s complexity and its divergence from the notion of “motion” in modern mechanics. Change occurs in four categories: place, quality, quantity, and substance. Change in place is local motion or translation, which can be rectilinear or circular; change in quality is alteration; change in quantity is increase or decrease; and change in substance is generation and corruption. While the first three types of change presuppose a permanent substrate and occur between contraries within the same category, generation and corruption take place between contradictories – that is, between terms where one is the total negation of the other. Generation is the transition “from non-substratum to substratum,” while corruption is the reverse (Physica, V, 1–2).

In light of this framework, the incommensurability between Aristotelian physics and Galilean mechanics becomes evident. Aristotle’s broad concept of change encompasses not only physical motion, such as the falling of a stone, but also biological development, such as a child growing into an adult. Furthermore, for Aristotle, actual motion is not a state – as in the modern concept of inertial motion – but a transition from one state to another (Kuhn 1985, p. X). Hence, Aristotelian physics is concerned not merely with quantitative aspects of phenomena, but also with their qualitative dimensions, which limits – though does not exclude – the application of mathematics.

Another key concept discussed in the Physics is that of the continuous (synechés). Motion can be continuous when it is uninterrupted, or consecutive when different motions follow one another without interval. Time, however, is always and only continuous, just like geometrical extension (space), whereas numerical series are discrete (Physica, V, 3). This doctrine allows Aristotle to refute Zeno of Elea’s famous paradoxes against motion. He observes that these arguments fail because they ignore the continuity of time and space: they assume, incorrectly, that time is composed of indivisible instants of rest or that space consists of extensionless points. Accordingly, Zeno’s paradoxes are inconclusive (Physica, VI, 9).

In the final books of the Physics, Aristotle defends two major theses: the eternity of motion and its heteronomy – its dependence on an external cause. The eternity of motion is supported by two arguments. First, any beginning of motion would itself be a change, and any cessation would also be a change, so motion would recur in either case. Second, since motion is measured by time, and time is also eternal, motion must be eternal as well. Any beginning of time would presuppose a “before,” and any cessation an “after,” both of which require time (Physica, VIII, 1–3). However, although these arguments apply to a continuous succession of different motions, Aristotle ultimately identifies eternal motion with the perpetual rotation of the heavens, because he equates “eternal” with “continuous” and determines that only circular motion is continuous (Physica, VIII, 6–9).

The heteronomy of motion is expressed in Aristotle’s famous axiom that “everything that is moved is moved by something else” – a statement that later became known as the principle of causality. He argues that nothing can move itself, since this would entail being both mover and moved in the same respect, which is a contradiction – being both in actuality and in potentiality with respect to the same motion (Physica, VIII, 4). Although this doctrine appears to contradict the modern principle of inertia – according to which a body in motion in a non-resistant medium requires no sustaining cause – it is rooted in Aristotle’s view of motion as a change of state, and in that respect, even modern physics still requires a cause for change.

From the heteronomy of motion, and the observation that an infinite regress of movers is impossible (since none would be sufficient to explain motion), Aristotle infers the necessity of a first unmoved mover – a being without magnitude but endowed with infinite power (Physica, VIII, 10). This entity, later in the Metaphysics, will be conceived as the pure actuality of thought – as life, and thus as god. In the Physics, however, the doctrine serves primarily to refute Plato’s notion that the heavens are moved by an immanent soul. Because it posits a cause that transcends sensible reality, Aristotle himself classifies this doctrine not under physics, but under first philosophy – that is, metaphysics.

In addition to analyzing motion in general – its characteristics and causes – Aristotle also offers a description of the universe in which we live, both as a whole and in terms of the parts into which he believed it was divided. In doing so, he developed what we might today call a cosmology, as well as a number of specialized natural sciences analogous to meteorology, geology, geophysics, mineralogy, and chemistry – fields we now collectively refer to as the earth sciences. The universe as a whole is the subject of De caelo, or On the Heavens (ouranós), a term which, for Aristotle, refers both to the outermost sphere containing the cosmos, the region extending from the fixed stars to the Moon, and the universe in its entirety. In this treatise, he begins by asserting that the universe is a perfect body: a three-dimensional solid, spherical in shape, and therefore finite – in the sense, as we have seen, of being complete (De caelo, I, 1; I, 5).

The heavens proper – that is, the region from the outer sphere to the Moon – are composed of a different element than the four traditional elements of terrestrial bodies (earth, water, air, and fire). This element, known as ether (aithḗr), is ungenerated and incorruptible, not subject to growth or decay, immutable, and naturally endowed with continuous and eternal circular motion. The term itself means “that which always (aeí) runs (theî)” (De caelo, I, 3). With this doctrine, Aristotle inaugurates a distinction that would dominate cosmological thought for nearly two millennia: the strict division between the heavens and the earth – two fundamentally different realms, composed of different substances, governed by different kinds of motion, and subject to entirely different laws. Celestial phenomena obey regular, necessary, and mathematically describable laws; terrestrial phenomena are governed by physical laws that apply “for the most part,” that is, with some degree of flexibility.

Within the heavens, the four terrestrial elements are arranged in a hierarchical order: at the center lies the Earth, surrounded successively by water, air, and fire – or more precisely, an inflammable form of air capable of being transformed into fire (De caelo, I, 8). Beyond the heavens there exists neither place, nor void, nor time – only certain entities upon which all being and life ultimately depend: the unmoved mover, or rather, as we shall see, a plurality of unmoved movers (De caelo, I, 9). The universe as a whole, according to Aristotle, is neither generated nor corruptible – it is eternal, not only because the five elements that constitute it are eternal, but also because the order in which they are arranged is eternal. This order is what the Greeks most precisely referred to with the word Cosmos (kósmos) (De caelo, I, 10–12).

The heavens, Aristotle claims, are ensouled – that is, they possess a soul and are therefore alive (De caelo, II, 1) – even though their motion is presumably caused by an entity that performs no action, being already complete in itself, and is thus immobile (De caelo, II, 12). Like every living being, the heavens possess a left and right, top and bottom, front and back (De caelo, II, 2); they are spherical in shape, rotate on their axis with regular and continuous motion, and contain at their center the Earth, which is also spherical but motionless (De caelo, II, 3–6).

This cosmological model, which Thomas Kuhn dubbed the “two-sphere universe,” was not Aristotle’s invention. It was common to nearly all previous cosmologists (with the sole exception of the Pythagoreans) and had been most thoroughly articulated in Plato’s Timaeus. It is thus inaccurate to attribute this model uniquely to Aristotle. According to his view, the celestial realm contains, first and foremost, the stars – later called the “fixed stars” – which appear to move uniformly, as if embedded in a single sphere. It also contains the planets, including the Sun, which exhibit irregular movements and were therefore called “wandering stars” (planētai in Greek). These celestial bodies are made of ether and move in circles because they are each embedded in a series of concentric spheres: the fixed stars are embedded in the outermost sphere, and each planet in an inner sphere (De caelo, II, 7–8). The Sun, also composed of ether, ignites the air beneath it through its movement, thereby producing light and heat. All the stars are ensouled, making them living beings; in fact, they are identified with the gods of Greek mythology (Metaphysica, XII, 8).

The stars are arranged in a hierarchy of perfection. The outermost sphere, which contains the fixed stars and is thus the most perfect, accomplishes its motion through a single circular movement. The other celestial bodies achieve their ends by means of multiple motions (De caelo, II, 12). Aristotle adopts the theory of Eudoxus of Cnidus, developed shortly before his own time, to account for the seemingly irregular planetary motions. Eudoxus proposed that each planet’s motion is the result of the combination of several uniform circular motions, as if the planet were carried by a system of nested spheres, each embedded in the next and rotating on a distinct axis. Eudoxus calculated that 26 spheres were needed to explain the motions of the seven known planets (Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Mercury, the Sun, and the Moon); his student Callippus increased the number to 33. Aristotle, believing these spheres to be material – composed of ether – found it necessary to insert additional “counter-rotating” spheres to prevent the cumulative mechanical interference caused by their contact, bringing the total to 55. With the sphere of the fixed stars, this results in a total of 56 spheres.

In this matter, Aristotle simply relied on the most advanced astronomical knowledge of his time. In the Metaphysics, where he demonstrates that every eternal motion (such as that of the heavens) requires a mover that is pure actuality – that is, always in act and therefore unmoved – Aristotle is compelled to posit 56 unmoved movers, one for each sphere (Metaphysica, XII, 6–8). Among these, however, one stands out as first and unique: the mover of the outermost sphere, the first unmoved mover. Because this sphere imparts its motion to all the others – adding its own to the motion already conferred by each sphere’s respective mover – the first unmoved mover is, by concurrence and priority, the ultimate cause of all cosmic motion. Aristotle compares it to a general directing an entire army or a master ruling an entire household (Metaphysica, XII, 10).

In De caelo, Aristotle also demonstrates the sphericity of the Earth using scientifically valid arguments, such as the Earth’s shadow profile observed during lunar eclipses. For estimating the Earth’s magnitude, he refers to the value provided by mathematicians, namely 400,000 stadia (De caelo, II, 13–14); a century later, Eratosthenes would calculate it to be approximately 252,000 stadia (around 39,690 km). In the second part of the work, Aristotle turns to the study of the terrestrial region, stating that it is inhabited by bodies composed of the four traditional elements, each of which is naturally subject to the various forms of change: generation and corruption, increase and decrease, alteration, and straight upward or downward motion. These are the natural motions, produced by weight and lightness, to which violent motions, caused by external agents – such as human intervention – are added. Thus, the region of the Earth is primarily characterized by the phenomenon of generation and corruption.

To this phenomenon Aristotle devotes an entire treatise, De generatione et corruptione, immediately following De caelo. There he shows that the four terrestrial elements themselves undergo generation and corruption, that is, they transform into one another. For this to occur, they must share a common substratum – what would later be called “prime matter” – whose existence Aristotle affirms, while also specifying that it never exists independently, but always as instantiated in one of the elements (De generatione et corruptione, II, 1). Each of the four terrestrial elements is defined by two of four fundamental qualities, which are arranged in opposing pairs: hot and cold, dry and moist. Earth is cold and dry, water cold and moist, air moist and hot, and fire hot and dry (ibid., 2–3).

The reciprocal transformation of the elements occurs when, for example, fire becomes moist and thus turns into air; air cools and becomes water; water dries and becomes earth; and earth heats and becomes fire. These transformations form a continuous cycle, driven by celestial motions – especially that of the Sun, which, revolving around the Earth on a plane inclined to the Earth’s axis (the so-called “oblique circle”), approaches and recedes from various zones, producing these transformations – and by the uniform motion of the outermost sphere, which guarantees the cycle’s continuity. Aristotle interprets this cycle as the earthly elements’ imitation of the circular motion of the heavens (ibid., II, 10).

A similar phenomenon occurs among terrestrial beings – namely animals and plants – formed by mixtures of the elements. These beings are generated through the Sun’s approach, which produces light and heat, and are corrupted by its recession. The succession of their generation and corruption, governed by the motion of the outermost sphere, thus also forms a continuous cycle. In the case of the elements, continuity is ensured by the persistence of the same substratum; in the case of living beings, by their reproduction – understood as an attempt by corruptible beings to participate in the eternity, and therefore divinity, of incorruptible beings (De anima, II, 4).

Of particular scientific interest is the treatise Meteorologica (“On the things above”), which discusses natural phenomena occurring in the region between Earth and the sky – that is, the atmosphere – as well as various terrestrial phenomena, for which Aristotle offers explanations that range from naïve to strikingly sophisticated. The area between Earth and the sky, according to Aristotle, is occupied by air: its upper part, in contact with the heavens, is hot and dry and thus easily flammable, while the lower part, nearer to the ground, is hot and moist. Two types of exhalation are produced in this air: a moist exhalation from water, which forms vapor, and a dry exhalation from the Earth, which forms smoke (Meteorologica, I, 3). Aristotle attributes various phenomena to these exhalations. Shooting stars, for instance, are explained as fragments of terrestrial exhalation that break apart and ignite due to heat; lightning is caused by the expulsion from clouds of inflamed terrestrial exhalation (I, 4). He offers a similar account for comets, which he sees as condensed terrestrial exhalations that, upon encountering lower layers of air, acquire the characteristic shape of a crowned star – although they are not true stars, which, according to Aristotle, exist only in the sublunar sphere (I, 7). The Milky Way, too, is attributed to the friction between Earth’s exhalation and the rotation of the sky (I, 8).

The exhalation of water, when acted upon by cold, gives rise to clouds, fog, rain, dew, frost, snow, and hail (I, 9-12). Underground concentrations of water give rise to rivers, which Aristotle also describes in geographical detail (I, 13). The sea, he claims, originates from water falling onto the Earth and collecting in the region that, according to the elemental structure of the universe, is assigned to water. The salinity of seawater is correctly attributed to the mixing of water with salt – though Aristotle believed this salt was also an exhalation that subsequently returned to the sea (II, 1-2). To support this claim, he offers two experiments: immersing a tightly sealed wax vessel in seawater, after which the water that seeps in is supposedly fresh; and adding salt to a vessel of water, increasing its density such that eggs float – just as ships float more easily on the sea than on rivers (II, 3). While the first experiment is implausible (since wax is not permeable), the second is scientifically accurate. Aristotle further supports the latter with reference to the “lake of Palestine,” i.e., the Dead Sea, where all objects float due to the high salt concentration. Other terrestrial phenomena are also traced to Earth’s exhalation: winds; earthquakes (caused by the sudden eruption of subterranean exhalation) (II, 7-8); thunder (the sound of inflamed exhalation striking clouds); and lightning (the subtle discharge of this exhalation from clouds). Lightning appears before thunder – even though it follows it – because sight precedes hearing (II, 9). The rainbow, on the other hand, is attributed to optical reflection: it arises from the reflection of light by water droplets suspended in the air, and Aristotle offers a detailed and somewhat complex theory of color decomposition in this context (III, 2-5). In Book IV of the Meteorologica – the authenticity of which is disputed – Aristotle explains various phenomena produced by the interaction of heat and cold, such as cooking, ripening, solidification, and liquefaction (IV, 2-6). Through the interaction of the four elements in various configurations, by processes of solidification and solution, he accounts for the formation of substances such as soda, salt, stone, clay, oil, wine, milk, and blood (IV, 7). Using similar principles, he describes the formation of “homeomerous” bodies (composed of uniform parts), such as metals and organic tissues (flesh, bones, tendons, skin, hair, and veins in animals; bark, leaves, and roots in plants). The combination of these produces “anhomeomerous” bodies – composed of different parts – such as the face, hand, or foot (IV, 10-12). From the perspective of modern science, it is unclear whether these explanations belong to physics, chemistry, or biology. Nonetheless, even in their frequent naïveté, they reflect an extraordinary effort to organize and clarify the entire field of human experience through a limited and coherent set of explanatory principles. Geometrical reasoning is not absent – particularly in Aristotle’s analyses of rainbows and winds – although quantitative measurement is lacking, likely due to the absence of adequate instruments or a general disinterest in this dimension of reality.In addition to Nature in general – both celestial and terrestrial – Aristotle devoted particular attention to Living Nature, that is, the world of plants and animals. This domain captivated him most due to its complexity, and it is in this area that he made his most significant scientific contributions, earning him the title of the founder of biology as a science. It is no coincidence that Charles Darwin, the architect of a true scientific revolution in modern biology through his theory of evolution – often seen in contrast to Aristotle – wrote in a famous letter to William Ogle (Feb. 22, 1882): “Linnaeus and Cuvier were my two gods, [...] but they were mere schoolboys compared to old Aristotle” (Darwin 1887, p. 427).

Aristotle’s series of biological treatises is preceded in the Corpus Aristotelicum by De Anima. This is not surprising, since by “soul” (psychḗ), Aristotle refers not only – or even primarily – to the human soul, but more generally to the principle that distinguishes living beings from non-living ones, and which is therefore common to all living nature (De Anima, I, 1). Thus, the study of the soul does not constitute psychology in the modern sense but serves as an introduction to the science of life – what we now call biology. At the beginning of Book II of De Anima, where Aristotle expounds his conception of the soul, he identifies its object as those natural bodies that possess the capacity to change “of themselves” and are also endowed with life (zōḗ), defined as the ability to nourish, grow, and perish (II, 1). This definition of life in terms of its most basic functions – those possessed by plants alone – reveals Aristotle’s intent to consider the phenomenon of life in its full scope, from the simplest to the most complex functions found in animals and ultimately in humans.

The soul is therefore defined as the “form” (eîdos) of such natural bodies, that is, of bodies capable of life (or “possessing life in potentiality”). By “form,” Aristotle means the structure, configuration, and internal organization that enable a body to live. He also defines the soul as the “act” (enteléchia), that is, the actualization or realization of this potentiality, specifying that it is a “first actuality” – a capacity that exists even when not actively exercised (e.g., during sleep). Since a living body is necessarily organized into organs, Aristotle further defines the soul as the actuality – or, in other words, the organizing principle – of a natural body equipped with organs (II, 1). This definition makes clear that the soul is not a substance opposed to the body or separable from it, as in the Pythagorean-Platonic tradition, but rather its intrinsic capacity to live, forming with it an inseparable unity – what we commonly refer to as the psychosomatic unity. A body endowed with a soul is not an inert entity to which the soul is externally added, but a living organism that would cease to be what it is if deprived of life. Aristotle conveys this concept powerfully when he states that the soul stands to the body as sight to the eye: just as an eye deprived of sight would be an eye only “by homonymy” (i.e., in name only, like a painted eye), so too a body without a soul would be a living body only in name. Thus, the soul is not a function or a set of functions that any body can perform; it is a potentiality inherent only in living, organized bodies. It is not merely the cause of life but also of being, since for living beings, being coincides with living. The soul is therefore the formal cause – the essence – without which a living entity would no longer be what it is (II, 4).

According to Aristotle, life is characterized by various functions, which he classifies into three groups: (1) those related to nutrition – growth, decay, and reproduction – common to all living beings and exclusive to plants; (2) those pertaining to movement and perception, proper to animals; and (3) those associated with thought and all activities that presuppose it, proper only to humans. Each class of functions has, as its principle or formal cause, a distinct type of soul: vegetative, sensitive, and intellectual (II, 2). However, these are not three separate souls coexisting in the same individual; rather, the more complex always includes the simpler within itself – what Aristotle calls “containing it in potentiality” (II, 3). This means the human soul encompasses the capabilities of the animal soul, which in turn includes those of the plant soul.

Aristotle devotes specific treatment to each of these functions, noting that nutrition resembles a form of cooking powered by vital heat, and that reproduction is the ultimate aim of all living beings – plants and animals alike – through which they participate in the eternal (II, 4). This demonstrates that by “end” or final cause, he does not imply conscious intention but a natural tendency toward self-preservation and full actualization. The end, therefore, coincides with the form – the perfection – of the living being.

Aristotle gives particular attention to sensory perception, common to all animals, which he defines as the reception of an object’s form without its matter – a kind of assimilation through the sense organs without material interpenetration. This applies to all five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch (II, 5–12). He then analyzes related faculties such as the “common sense” (the perception of features shared by multiple senses), awareness of perception, and imagination – all of which are shared by animals (III, 1–3).

Next, Aristotle examines the uniquely human faculty of thought, which he hypothesizes to be separable from the rest of the soul in two famous and much-debated chapters that veer more toward anthropology or metaphysics than biology (III, 4–5). Finally, he considers the principle of animal locomotion, which he identifies with the faculty of desire (órexis), always presupposing some knowledge of its object – whether sensory or intellectual (III, 7–10). This domain, too, especially insofar as it involves rational desire and action (prâxis), borders on anthropology and practical philosophy.

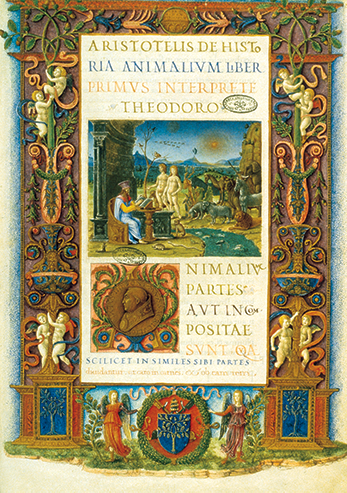

The Aristotelian treatise on plants – De Plantis, mentioned in ancient catalogues of his works – has not come down to us, if it ever existed (the treatise of the same name preserved in the Corpus Aristotelicum is not by Aristotle). Fortunately, however, we do have the History of Plants by his student and successor Theophrastus. More importantly, numerous treatises by Aristotle devoted to animals have survived: the most significant among them are the Historia Animalium (in ten books, though the authenticity of some is disputed), De Partibus Animalium (in four books), and De Generatione Animalium (in five books). In the title of the first work, the term historía should be understood not in the modern sense, but in the Greek sense of description, compilation of observations, and presentation of data. Indeed, the work contains an immense amount of descriptive content – concerning approximately 500 animal species – including anatomical structure, reproductive processes, and behaviour. It therefore partly overlaps with the other two treatises, raising questions about their interrelation. Aristotle himself clarifies this relationship in a passage from De Partibus Animalium, where he states that in the Historia he described the parts from which each animal is constituted, and that in De Partibus he will now explain the causes of why each of these parts is as it is (De Partibus Animalium, II, 1). It would seem, therefore, that De Partibus Animalium and De Generatione Animalium provide causal explanations – the “why” – of the phenomena presented in the Historia, which is devoted to the “what”. However, this division is not strictly observed, as the Historia also often includes genuine causal discussions, making it an independent treatise in its own right.

Aristotle’s primary focus lies in the description of animals’ “parts” – that is, the organs and tissues that comprise them. He draws on the testimony of numerous specialists – breeders, fishermen, hunters, travellers, butchers – as well as his own direct observations, sometimes carried out through dissection. In one passage, he notes: “Observation is difficult, and one can obtain adequate information, if one is genuinely interested in such matters, only from animals that have been strangled after being emaciated” (Historia Animalium, III, 3, 513a 12 ff.). In such specimens, blood remains in the veins, which are more visible if the animal has been emaciated, allowing observation of a state as close as possible to that of the living animal. With this method, Aristotle inaugurated the study of both animal and human anatomy.

In analysing animal parts, Aristotle compares individuals of the same species, different species within the same genus (e.g., various species of fish or birds), and different genera (e.g., mammals and fish). The distinction between “species” and “genus” is not rigidly fixed, appearing to be based more on logical classification needs than on any belief in the objective reality of such groupings. Among animals of different genera, one may observe analogies – that is, identity of function between morphologically distinct organs (e.g., lungs in mammals and gills in fish). Analogy thus proves a powerful heuristic tool, making Aristotle the founder of comparative anatomy. His contributions to this field were likely consolidated in a set of “Anatomies” (Anatomíai), now lost, to which he frequently refers, especially in the Historia Animalium.

Through such analyses, Aristotle develops a comprehensive theory of animal parts: the four elements and their fundamental qualities (hot and cold, dry and moist), through various combinations, give rise to the homogeneous parts (homoiomerê) – the tissues (blood, flesh, bone, skin, cartilage, etc.). These tissues, in turn, combine to form non-homogeneous parts (anhomoiomerê) – the organs (heart, lungs, brain, liver, etc.). These organs are then assembled into a single organism – a body composed of organs. The unifying principle binding these diverse parts into a coherent whole is the function they serve: tissues exist for the sake of organs, and organs for the sake of the organism. The concept of function thus leads directly to the explanatory framework of biological phenomena, making Aristotle’s biology – by modern standards – not only comparative anatomy but also a genuine physiology. For Aristotle, the study of animals is a proper science – that is, a knowledge of causes, which, as set out at the beginning of De Partibus Animalium, comprise all four causes distinguished in the Physics: material, formal, efficient, and final. Among these, the formal cause – i.e., the form, the structural unity of animals and the organization of their bodies for the performance of vital functions (growth, preservation, reproduction) – is the most important.

The central principle of Aristotelian biology is that function explains structure: to understand the anatomy of an organ, one must consider its purpose. Even the material composition of organs – important as the material cause – forms part of a necessary structure, though it is a hypothetical or conditional necessity, subordinate to the fulfilment of an end. For instance, teeth or horns must be hard because their function demands it. Since all bodily functions are directed toward the preservation of the individual and, via reproduction, the preservation of the species, the formal cause – that is, the being of the organism and of the species – coincides in biology with the final cause. This clarifies the nature of Aristotelian teleology: it is not anthropocentric or providentialist, but an intrinsic finality within each species, directed solely toward its own continuation. Even where Aristotle appears to assert a hierarchy – for example, in Politics, I.8, 1256b 15–20 – suggesting that plants exist for animals and animals for humans, he refers only to the incidental utility one species may offer another, not to a genuine teleology internal to those species. Nonetheless, Aristotle does assert the superiority of humans over other animals – due to upright posture and the complexity of their functions – and posits a continuous scale of beings (scala naturae), descending from humans through the animal kingdom to plants and ultimately to inanimate objects. In this scale, differences between adjacent species are minimal and often imperceptible (Historia Animalium, VIII, 1; De Partibus Animalium, IV, 5).

Aristotle was less successful, however, in his physiological theory concerning the primacy of the heart over all other organs in higher animals. He attributed a fundamental role to vital heat as the source of life: according to him, vital heat enables digestion – conceived as a form of cooking – which transforms food into blood, which then nourishes the entire organism. The heart, he argued, is the origin of this heat and the site where blood is formed, making it the central organ of the living being (De Partibus Animalium, III, 4). This view excluded the rival theory – advanced by the Pythagorean Alcmaeon and later adopted by Plato – that the brain is the principal organ. For Aristotle, the brain serves only to cool the blood – a secondary and opposite function to that of the heart. Aristotle, unaware of the nervous system and the brain’s role in it, maintained the heart as the body’s central organ, receiving sensory input via the veins. He justified this claim by observing that the heart is the first organ to form during embryonic development. Although ultimately incorrect, this theory positively influenced William Harvey, who, having studied at the Aristotelian school in Padua, assigned a central role to the heart and went on to discover the circulation of blood (De Motu Cordis, 1628).

In his investigation into animal species, Aristotle aims above all to discover their formal cause – that is, their essence. To this end, he makes extensive use of the Platonic method of division, which he learned at the Academy. However, he transforms it from the simple dichotomy employed by Plato into a method involving multiple differentiations among species, continuing until he identifies the unique difference sufficient to distinguish each species from all others – its “specific difference,” which constitutes its essence (De Partibus Animalium, I, 2). Although Aristotle's purpose is not merely classificatory but fundamentally explanatory and definitional, the outcome is a systematic classification of animals that remained influential for centuries.

He divides animals first into those “with blood” and “bloodless,” a distinction roughly corresponding to the modern categories of vertebrates and invertebrates. Among blooded animals, he classifies them by reproductive method into viviparous and oviparous. The viviparous – corresponding to modern mammals – are further subdivided into quadrupeds, cetaceans, and bats (notably, Aristotle correctly identifies whales and dolphins as mammals). Oviparous animals are distinguished by respiratory type: those with lungs (reptiles and birds) and those with gills (fish). Bloodless animals are divided into mollusks, crustaceans, gastropods, and insects. Regarding insects, Aristotle accurately describes their reproduction through larval stages but erroneously attributes spontaneous generation from mud to many species.

Reproduction is the subject of an entire treatise, De Generatione Animalium, in which Aristotle analyzes sexual differentiation, reproductive organs and their functions, embryonic development, and secondary sexual characteristics. He applies the fourfold causal framework to generation as well: male semen (sperm) is assigned the roles of both efficient and formal cause, while the female’s menstrual fluid functions as the material cause. Semen, considered the most vital component of blood and produced through the highest concentration of vital heat, can only be generated by males – who, according to Aristotle, possess more vital heat than females. Semen contains what he terms pneûma, a kind of warm breath evidenced by its foamy appearance, which transmits a series of mechanical impulses to the menstrual matter, animating it and guiding its development into the adult organism (II, 2). Thus, sperm acts as the efficient cause but also transmits the form – i.e., the soul – of the parent, thereby functioning as the formal cause. Furthermore, the impulses it transmits are oriented toward the adult form, making the adult organism the final cause.